Authors: Nehir Akdemir, Alihan Emre Kılıç

Abstract

The history of prison reform and developing prison architecture in the Ottoman Empire during the 19th century is a relatively recent field of study. Prison structures planned for several Anatolian regions must be examined in order to fully comprehend the impact of the shift started with the empire's general reforms on the Ottoman prison architecture field. The Tanzimat period came with a number of criminal laws, which not only opened the way for the transition from physical punishment to incarceration, but also led in the building of functionally built prisons in the Ottoman Empire's main regions. Inspectors' criminal rules, ordinances, regulations, and assessments formed the foundation of Ottoman prison reform, which aimed to systematize prison architecture, spatial distribution, staff, and prisoners' living standards. This article examines the gradual and inconsistent progress of Ottoman prison reform in the late Ottoman Empire, with an emphasis on the central prisons of Istanbul and Ankara. By analyzing the function of model prisons constructed in the late 19th century, this paper aims to provide both fundamental and circumferential views of the development of Ottoman prison systems.

1. Introduction

Several investigations have indicated that ever since the early stages of Abdülhamid II's time in power in 1876, there has been a flurry of building construction all throughout the country, which include healthcare facilities, military quarters, industrial plants, rail systems, places of worship, city halls, clock towers, and education institutions. Prisons were a significant but largely neglected architectural group during this time of intensive construction. Prison architecture and construction was seen and performed as a significant alteration project.

The 18th century Western ideas and changes on penal and prison systems did not reach the Ottoman Empire until the early 19th century. Before this time, the Empire's architectural places of incarceration were generally in temporary places known as ''mahbes'' or ''zindan'' (dungeon). Such temporary locations were primarily found under basement levels of fortifications, basements of khans’ palaces, docks, administrative offices, or mansions of local officials. These locations were not intended to be spaces where strict punishments were enforced, also not for the custodial sentences to be served in these places as the primary way of punishment throughout this time period. [1]

Prison sentences were originally adopted as the primary way of punishment in the Ottoman Empire following the Tanzimat reforms. The Tanzimat reformers' efforts at centralization and bureaucratization, as well as the announcement of the new version of criminal laws in 1851 and 1858, not only laid the foundation for the transition from corporal punishment (physical punishment such as flogging) and capital punishment (death penalty) to prison sentences, but also enabled the emergence of a strong and new system of rules of criminal justice. [2]. After the reform effort, the first prison, known as "Hapishane-i Umumi" (Central Prison), was established in 1831 in a section of Istanbul's Ibrahim Pasha Palace. Being part of the jail reform movement, laws were established in 1840, 1851, and 1858, starting in 1838. As a result, the term "imprisonments" was introduced into Ottoman legislation as a form of punishment. Changes in criminal legislation eventually resulted in the alteration of prisons. This reform campaign grew into a significant endeavor to construct the 'orderly and excellent' central prisons which were planned to be constructed all across the Ottoman territories, beginning in especially during the reign of Abdülhamid II. [3].

1.1. Prison Reform

Being a part of the Westernization and reform activities, various decrees were issued addressing the insufficiency and shortcomings of living conditions of prisoners. The new criminal laws passed in 1838 were the first, backed by many others in 1840, 1851, and 1858. The most extensive prison law was a 97-item decree published in 1880 under the headline of "Regulation on the Internal Affairs of the Prisons in Memalik-i Mahrusa-i Şahane." This decree divided prisons into three categories: "detention centers, prisons, and central prisons." Construction of a detention center and a prison for every town, county, and province, as well as central prisons in suitable locations for inmates condemned to more than five years, was also required. [4]. The order not only defined specific requirements for inmates, but it also imposed new procedures, including separating criminals based on their crimes; and the development of work spaces (workshops), distinct wards for minor and female convicts, and specialized places for worship, as well as infirmaries for medical treatments of sick prisoners with proper hygiene, ventilation and lighting conditions. The previous old dungeons could not meet the revised legislation's space requirements, like different cells for each inmate and the availability of work areas. Therefore, the need of modern prison buildings fitting into the requirements of the new law has risen and people started to work on constructing “orderly and excellent prisons, like the ones in Europe”.[5]. Auburn State Prison (New York, 1816), Eastern State Penitentiary (Philadelphia, 1825), Pentonville Prison (London, 1842), Fresnes Prison (Fresnes, 1898), Pittsburg Western Penitentiary (Pennsylvania, 1884), and Newgate Prison (London, 1785) are all known cases formed under those guidelines in the 19th century, and are also regarded as the basic models for prison plans.

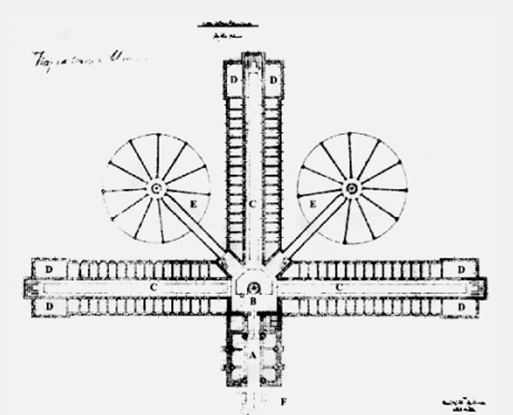

Figure 1

Plans of some of the model prisons in Europe and America

2. Ankara Central Prison

Ankara Central Prison is one of the prisons that has been modernized as result of the prison reform. It was agreed around the late 19th century that, with the aim of meeting the architectural requirements specified by the law, renovations to existing prison structures would be insufficient, and that new prison constructions would be needed. As a result, major prison constructions started across the country. An examination of completed projects, particularly around the start of the 20th century, reveals that uniform prison prototypes planned to be constructed in each and every place all over the country had been created. [6]. Ankara was among the cities in which this transition in prison architecture could be observed.

2.1. Central Plan Proposal for Ankara Central Prison

The old prison building is in disrepair, necessitating the construction of a new prison facility. [7]. The proposal, which has been produced on two pages for Ankara Prison, comprises of drawings that include a partial base plan, floor plans, cross-sections, and elevations. According to the façade designs and floor plans, the prison is a two-storey structure with a three-storey inner building in the middle and an outdoor courtyard design. "12 November 1895" date is inscribed on the left side of this paper. [8].

Figure 2 - Plan and Sections of the proposal

A. Ground Floor Plan: 1. Security-enhanced ward, 2. Room for court recorder, 3. Administrative office, 4. Ward for custody, 5. Room for guard, 6. Isolation Cells, 7. Gasilhane (Room for burial preparation in Muslims), 8. Toilets, 9. Kitchen and Laundry, 10. Kitchen, 11. Prison for women, 12. Garden, 13. Courtyard, 14. Inner courtyard, 15. Ward, 16. Room, 17. Interrogation room, B. Hospital, 18. Rooms for sick prisoners, C. Section of the foundation wall, D. Scale 1/200, E. 12 November 1895 [9]

Figure 3 - Elevations and Plans of the Proposal

F. Second floor plan of the inner structure, 19. Ward for the prisons convicted for first degree sentences, G. Third floor plan of the inner structure, H. Orthographic projection, I. Façade of the inner structure.

The ground floor of this distinct section serves as a questioning room, while the higher floors house convicts accused of severe crimes. According to the upper floor plan as well as the other exterior façade drawing, the part of the building that may be regarded the main entrance seems to be as tall as two storeys. Whereas the management units and cells that house one prisoner are located on the ground level of the main building, the access to the female prisoner units is located on the building's backside.

Although it is part of the main building, the female inmates' section is constructed as a closed block that has its own courtyard. Even though females can be considered as a minority compared to general population, they needed a separate place for their safety and in order to give female prisoners privacy of their own.

The 1880 Prison Regulation provided extremely specific regulations for constructing gender specific division within Ottoman prisons. This would also come as no big surprise that separate spaces for different genders are the key element with most modern prisons. Gender - based place is also deeply embedded in Middle Eastern and Islamic cultures. Female inmates should be watched by female guards, and specific policies must be provided for imprisoned women who are pregnant or breastfeeding. [10]

The numerical values about the inmates are as follows; there are a total of 2.196 prisoners, 59 of them are female in Ankara. Moreover, the total number of prisoners that committed ‘’less-serious crimes’’ is 800 and 38 of them are female, also the total population of inmates that committed ‘’serious crimes’’ are 1.375 and 21 of them are female. [11]. Considering the fact that, female inmates cover a much less portion, as compared to the total number of prisoners, state prison officials invested significant amount of time, effort and resources developing a prison space that is only for female prisoners and their needs.

The façade and section drawings clearly show the features of the prison's doors, windows, door frames, and roofing. The windows on the front enable daylight and air to enter the wards. According to the sections of the constructions, the roofing was constructed as a basic hip roof over certain elements of the structure, while it was built as a porch roof over other elements.

The assessment of the new Ankara Central Prison project reveals that the national government intended to conform the new facility to the requirements needed by the 1881 extensive prison reform. For instance, single-prisoner cells were viewed in the context of the law, but due to their shortage, wards were also included in the design. A distinct female ward was also created, but no room was planned for young minor prisoners. Workshops, which are crucial for convicts to work on throughout the day, were not incorporated in the planned Ankara Central Prison design proposals.

2.2. Radial Plan Proposal for Ankara Central Prison

As stated above, the old prison was in a shape that it couldn't operate, and it was better to construct a whole new prison, because the fixing the old one would be take much more time and effort. The radial plan proposal was one of the options that could be built for Ankara Central Prison.

Figure 4 - Plan of the proposal

A. Administrative, hospital and workshop units, B. Courtyard for hospital, C. Bath, kitchen, ablution and toilets, D. Courtyard for prisoners, E. Wards for men and women prisoners, F. Courtyard for women prisoners, G. Kitchen, ablution and toilets, H. Courtyard for the prisoners convicted for first degree sentences (for short term), I. Ward for the prisoners convicted for first degree sentences, J. Courtyard for the prisoners convicted for first degree sentences (for life-long), K. Kitchen, ablution and toilets, L. Garden, M. Administration office rooms and observation tower. 1. Entrance of the men prisoners, 2. Ward for gendarmerie, 3. Room for gendarmerie commander, 4. Prison Secretary, 5. Room for prison warden, 6. Janitor room, 7. Workshop, 8. Toilets, 9. Pharmacy, 10. Hospital ward, 11. Exit to courtyard, 12. Doctor room, 13. Caldarium, 14. Tepidarium, 15. Frigidarium, 16. Kitchen, 17. Ablution room, 18. Toilets, 19. Ward, 20. Ward for the prisoners convicted for homicide 21. Ward for women, 22. Entrance to women prisoners, 23. Ward for the prisoners convicted for first degree sentences (for short term), 24. Ward for the prisoners convicted for first degree sentences (for long term), 25. Mosque, 26. Guard rooms, 27. Observation tower

Figure 5 - Section and Elevation of the proposal, 1916

The radial plan structure, which is made composed of six radiating wings spreading from a hexagonal core in the middle, is also set in a hexagonal courtyard. Courtyards were intended for the open areas between the wings. Every one of the six wings seems to have a distinct purpose. The administration arm includes a gendarme ward, a room for the gendarme's commander, a prison secretary, a prison warden, a janitor's room, a workplace, a pharmacy, a hospital ward, a walkway, and a doctor's room.

In each of the three arms housing the service units, there is a bathroom, a kitchen, a hygiene area, and restrooms. The other two arms were planned to be prison wards. Inside one of the arms, there is a religious worship building with its own entrance. The spaces in between arms are courtyards that vary based on the categorization of the inmates.

In the prison, there is a division between male and female convicts, as well as different levels of security. Male convicts are assigned to wards depending on the grade of the crime they committed. It can be observed that these inmates were classified based on their crimes as prisoners on short-terms, prisoners on life sentences, and prisoners sentenced to death penalty. Because there is a lack of transition in between wards and the wards are located back-to-back, the female prisoners' wings are totally isolated. [12]. The gender-based regulations are valid in this proposal too, as in Central Prison Proposal. They needed to construct a prison regarding the female prisoners’ safety and well-being separately from male prisoners in order to prevent unwanted incidents between men and women inmates like rape, sexual assault etc..

The hexagonal structure in the middle of the complex serves as the entrance to the prison's courtyards, wards, and mosque. A watchtower and guard rooms may be found in this part. The tower is accessible through a spiral staircase placed between the tower and the guard rooms. The tower being designed to be taller than the radial arms, as visible in the sections, is significant for the monitoring and control of inmates in the courtyard.

Yet, it is true in the sense that the proposed Ankara Central Prison project is more than just simply a prison structure; it is a prison complex that includes the healthcare, service, and administration divisions. It is not a structure that only serves as a place for prisoners to stay within their sentences. It is designed as a complex that ensures that all the needs of prisoners are taken care of. For example, the prison complex provides healthcare, prayer spaces and open courtyards that offer fresh air to inmates. It is obvious that an effort was made to adapt to the spatial constraints outlined in the reforms.

3. Istanbul Yedikule Central Prison

Over the course of the rule of Abdülhamid II, the necessity for a new jail had become a major political issue. The choice of Yedikule Fortress for the place for a new prison conforming to Western norms is extremely noteworthy since it was the symbol of fear and dread because it was the place that many significant historical figures were executed. [13]. For example, the young Sultan Osman II was one of Yedikule Dungeons' most renowned victims, held as a prisoner and executed there by the Soldiers in 1622. David Megas Komnenos, the last Emperor of Trebizond, was one of several figures who were killed, as well as Constantin Brâncoveanu of Wallachia and his family, King Simon I of Kartli, and some of the important Ottoman pashas. (Meyer-Plath & Schneider 1943, p. 42. Meyer-Plath, Bruno; Schneider, Alfons Maria (1943), Die Landmauer von Konstantinopel, Teil II (in German), Berlin: W. de Gruyter & Co.). The first of the proposed Istanbul Yedikule Central Prison projects is a complex developed by architect August Carl Friedrich Jasmund. The second is Ferik Blunt Pasha's proposal, which was provided as an appendix to his report. The third proposal is an example of a radially designed project that is believed to have been completed by Architect Kemaleddin Bey, although it must be viewed in context of the two preceding proposals previously allocated for this location. Those three proposals for Yedikule Central Prison are seen to be proof for a distinctively Ottoman approach to 'modernizing' the Empire by developing their original architectural design solution.

3.1. Site Selection for the Istanbul Yedikule Central Prison

Abdülhamid II issued a special order on March 2, 1893, the building of a new prison complex in Istanbul that would be "orderly and excellent, like the prisons in Europe." A new place for a central prison in the internal courtyard of the Yedikule Fortress was proposed in a document issued on September 28, 1893, due to insufficiency of the original prison in fulfilling the outlined spatial requirements and the fortress was strategically placed in a central place in town. According to this document, since this new location was outside of the city yet totally enclosed by walls of the city and completely isolated from outer distractive stimulants, it was like it was cut out for being a prison site and it was seen reasonable and acceptable for an 'excellent' central prison. Also, Abdülhamid wanted to change the unpleasant memories and impressions of Yedikule Fortress, which are associated with fear and terror, by replacing them with a contemporary, sophisticated model prison in the capital.

3.2. August Jasmund’s Istanbul Yedikule Central Prison Proposal

Jasmund's proposal is not just a single prison building, but rather a group of structures, some inside and others beyond the fortress walls. Hospitals, baths, and houses of worship are all placed inside the city walls as independent modules as components of the prison complex. The area beyond the city wall is dedicated to administration, military security, and service elements.

All of these facilities are surrounded by fortress walls, and the fortress towers were most likely built to serve as watch towers. The fortress has eight stairs that connect directly to these fortress walls. The ground floor plans show four interconnected structures inside the walls of the city, including a prison, an infirmary, a bath, and a religious institution, all set within a consistent landscape design which is based on Western models. In the wide open areas within the fortress walls, prisoners have complete freedom of movement. There might be two primary causes for this: To begin with, the usage of bathing, worship, and healthcare facilities outside the main prison structure might intended to be done collaboratively and under military supervision, or secondly a much freer flow of circulation for inmates could have been intended, with real supervision and monitoring undertaken inside the fortress walls. Even though they are prisoners, they are also humans and they need some ‘freedom’ within their daily activities. Them being prisoners does not mean that their movement and circulation should be completely restricted. For sure there will be some restrictions but there needs to be some flexibility and a relative freedom for prisoners’ mental health, since they are trying to be rehabilitated.

The doorway to the left of the prison provides access to buildings outside the fortress. Because there are no cross-sections or façade drawings, it is unclear how many levels the prison complex has. However, the presence of two separate floor plans in the archive shows that the structure was meant to have two levels. The prison, located in the heart of the fortress, is made up of two major components arranged in a T configuration. The main entrance to the penitentiary is on the side directly facing the spires.

Figure 6

Prison Ground Floor Plan: A - Prison, 1 - Workshop, 2 - Storage, 3 - Room for soldiers and guards, 4 - Isolation cell

Figure 7

Prison Second Floor Plan: A - Prison, 1 - Ward for 10 prisoners, 2 - Isolation cell, Room for guards

Even in solitary cells, which have two windows, they made sure that prisoners get good ventilation and natural daylight. The prison's top floor layout has thirty wards, each to be accommodating ten inmates, four solitary cells, three guardrooms, and six bathrooms. The blue area is considered to be a gallery that follows the hallway in the middle and is restricted for circulation. It was very likely supposed to offer monitoring and controlling across floors. Because of the fact that only the term "prisoner" is used in the divisions in the prison layouts, it is impossible to identify if there is a particular section for female or minor inmates in the prison complex.

The most essential element to underline in Jasmund's prison proposal is that it is a complex of facilities that includes a place for worship with a mosque, church, and synagogue, administration and military security facilities, and service units (laundry and kitchen). Jasmund's proposal, the first campus prison plan developed with a profound comprehension, is the first indication of a desire to address the fundamental requirements of convicts, in accordance with the prison reforms imposed as a result of Abdülhamid II's decrees. The structures that surround the prison strongly demonstrate that efforts have been made to accommodate the health, hygiene, and other needs of inmates.

The presence of a house of worship that combines a mosque, a church and a synagogue might be seen as an indication that non-Muslim inmates and their rights are also taken in to consideration and equally respected as Muslim prisoners. Since the Ottoman Empire was a wide, multi-national, and multi-religious empire, it had an extremely complex social structure. Actually, the Ottoman Empire was Europe's and Asia's most religiously diverse empire. Even though the Ottoman Empire was aware that this variety in the society can be detrimental to the Empire, they granted protections and privileges to the minority by classifying them fairly because the Ottoman Empire used to have a large number of people who belonged to various ethnic and cultural backgrounds, spoke various languages, and embraced diverse beliefs and religions. Therefore, the Empire required to handle all individuals with peace and unity within the nation in order to accomplish their goals internationally and they took advantage of the Empire's multiplicity. These worship houses inside this prison that serves various religions were probably planned with this aim of bringing the old socially rich and diverse Ottoman Empire back.

Another notable characteristic is the existence of workshops devoted to prisoner usage. It is critical to provide workshops in the prison for inmates to work in. Working areas and workshops, fashioned after models in America and Europe, are 'rehabilitation' spaces where inmates may learn new skills, spend their free time, and make money.

Moreover, the landscape layout is significant, as it was not seen in the Ottoman Empire prior to the 19th century. The design incorporates circular and oval shapes, as well as a pool. The concept is rare for a prison.

Despite the fact that Jasmund's proposal goes above previous prison designs and is a model of a "orderly and excellent" prison, as Abdülhamid II requested, it does not entirely conform to the prison requirements outlined by the 97-article decree of 1880. This regulation specified that prisoners to be held in separate cells based on the degree of their crimes, as well as different cells for women and children. These spatial configurations are not part of Jasmund's proposal.

3.3. Ferik Blunt Pasha’s Istanbul Yedikule Central Prison Proposal

The proposal by Ferik Blunt Pasha is a prison complex structure with many components and also the primary prison building designed with a radial layout. The complex is set in a quadrangular courtyard and includes a primary prison structure with a separate courtyard in the middle, a medical center, a police department, guard rooms, a mosque, housing for the imam, a bakery, a kitchen, a bathroom, a storage, and lodgings for prison wardens. The prison complex has only one entrance, which makes it accessible to both the primary prison and the other facilities in the complex.

The primary prison building is an eight-block radially designed structure with an octagonal shaped inner courtyard in the center. A supervisor's room, a guest room, a clerk's room, a prison warden room, administration rooms, a temporary detention room, a guard room, a library, and storage rooms for inmates' possessions and clothing are all located near the building's entrance. This block provides entrance to the inner courtyard in the heart of the main prison. Vertical circulation is provided via a stairway in the inner courtyard. Workshops for convicts are located on the other side of the block from the main prison entrance to the inner courtyard. The other six units that radiate from the inner courtyard are occupied with inmate cells.[14].

Each block has 40 solitary cells, and the layout of the prison building's entry level indicates that 240 solitary cells are on this floor. Each block has a door that leads to the octagonal shaped courtyard that surrounds the primary prison structure.[15]. Courtyards near these doors, created to let convicts to spend time outdoors, are isolated from the center by blocks.

Similar to Jasmund's project proposal, Ferik Blunt Pasha's prison plan also mirrors emerging legislation in Europe and America. This notion is reflected in the architecture of the prison complex with side purposes, as well as the building of workshops for convicts' labor and solitary cells.

Thanks to the cell-based radial plan type with wings radiating out from a focal place, Blunt Pasha's design, which also addresses the design problem as more than just a prison building but a campus project, is a step beyond Jasmund's project. The radial layout, which was firstly applied at Philadelphia Eastern State Penitentiary, offers spatial efficiency because it is simple to arrange cells on the hallway in each wing based on the inmates' crimes. Another improvement is the transformation of the areas in between the wings to open courtyards where prisoners may enjoy some fresh air. According to Blunt Pasha's design, administration and different service units (including education and healthcare) are located in the central building, whereas accommodation units are placed in wings separate from this block.

One notable architectural difference in Blunt Pasha's project proposal is that the blocks housing the cells allow for the isolation of inmates based on the grade of their crimes. Even though this distinction is not explicitly stated in the plan's description, it may be assumed that it was evaluated because Blunt Pasha's report highlighted the significance of this division. The Ottoman prison legislation, like the Western models on which it was founded, demanded the division of inmates depending on the seriousness of the crimes committed, and also separate quarters for female and minor young inmates.

3.4. Architect Kemaleddin and His Student Çatalcalı Fehmi’s Istanbul Yedikule Central Prison Proposal

For the Yedikule Central Prison, the radial plan type had become a suitable option. Research on versions of the radial plan scheme by both architect Kemaleddin and his student reveal that this layout was regarded as a fundamental model that can satisfy the needs of the prison reform. In contrast to the main structure of the radial plan type, Kemaleddin altered his design by incorporating three long wings as prison cells and two short wings as workshop spaces, rather than wings of equal length in all directions.

The project proposal uses a radial layout with three long arms that each include 30 solitary cells. The number of storeys in the structure is unknown because there are no cross-sections or façades drawings. There is also a third floor layout, implying that the building might have four levels.[16]. In this example, the building may be considered to have a total of 360 solitary cells. The entrance is from the short wing, which leads to the octagonal grand hall in the prison complex's center. The rooms located in the short wing are for administrators alone. The passageways in this hall lead to all the other wings. [17].

The staircases in the middle octagonal courtyard and at the end of the long wings allow vertical circulation between the levels. Large secluded spaces may be found on the two short wings accessible from the octagonal hall. These were most probably meant as workshops for inmates to collaborate on works.

Two further drawings were discovered with the title "From the Planned Central Prison Project" in addition to the project. The two drawings, a second floor plan and a front façade drawing have the signature "Çatalcalı Fehmi, Engineering School Seventh Year Student" and are undated. The project, like Kemaleddin's, is structured on a cell basis.

Rather than the workshops in Kemaleddin's proposal's radial short wings, his student's proposal has circular sections attached to the main facility's center by corridor-like connections. These circular constructions might house workshops or act as locations for inmates to get fresh air and workout outside. The wide gaps at the ends of the wings are also noticeable. These vast areas, which face one another, may perhaps be work areas for the convicts, however this cannot be determined from the drawings. In addition, like Kemaleddin's layout, this proposal has galleries along the central axis of the cell wings, which allow for vertical circulation. Narrow passageways offer entry to the cells on the higher floors.

Across from the prison gate a single-domed mosque is present. According to the façade designs, the block in the centre of the structure is taller than the units in the other parts and has an octagonal roofing. Watchtowers can also be seen at the endpoints of the long wings that house the cells. The height of these spires, each crowned with a dome, is roughly equal to that of the octagonal domed building at the prison's center. One of the creative solutions to this recently faced 'central prison' issue is the use of facade components such as a high pointed-arch entry with a dome and two domed-towers on the corners.[18].

Figure 8

Istanbul Prison Project drawn by Architect Kemaleddin: A - Short wing containing administrative rooms, B - Octagonal central hall, C - The wing consists of isolation cells, D – Workshops

Figure 9

‘’A prison project’’, Plan, drawn by Çatalcalı Fehmi, 7th grade student of the school of engineering (hendese-i mülkiye-i şahane): A - Short wing containing administrative rooms, B - Central hall, C - The wing consists of isolation cells, D - Workshops (?), E - Workshops or exercise spaces (?), F - Mosque

Figure 10

‘’A prison project’’, Elevation, drawn by Çatalcalı Fehmi, 7th grade student of the school of engineering (hendese-i mülkiye-i şahane)

Figure 11

All proposed projects for the Istanbul Yedikule Central Prison

4. Conclusion

19th century Ottoman prison design and architecture, that had not previously been thoroughly studied, comes out as a wide field which can have an impact on the production of this century's architectural history. The prison architecture of the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century, which is the focus of this article, is significant because it helps to provide a fresh viewpoint. The extensive prison construction projects that encompassed the whole Ottoman territory, as well as the prison reform movements under Sultan Abdülhamid II's rule, are remarkable.

Prison project proposals planned to be constructed in many Anatolian provinces, some of them have been put in place and some have stayed on paper, are a subject which requires to be researched in order to comprehend the impact of the transition started by the Empire's prison reforms on the Ottoman modern built environment. According to researchers, the Ottoman Empire stayed abreast of the change of the notion of punishment and correctional facilities for criminals. The alteration of the Ankara and Istanbul Yedikule Central Prisons, the topic of the article, helps to track the Ottoman Empire's stages in the prison reform process and evaluate the spatial configuration development.

According to regulations and correspondences researched by experts, the justice system, especially the prison reform, was a significant concern during the reign of Abdülhamid II. The modern and innovative prison designs created for all Anatolian provinces should be evaluated within the framework of the government's aim of not falling behind with the modernization effort in Europe. Prisons constructed in America and Europe during this time period were developed based upon fundamental methods to inmate rehabilitation. These policies arose as rules of extreme isolation, extreme quietness, or even both, necessitating cell-based space organization rather than wards.

The prevalent notion was that inmates would be rehabilitated via work and religion throughout the day and resting and relaxing in solitary cells during nighttime. The fundamental aspects of the new model prison systems that emerged in the Western world at the late 19th century also included imprisonment of prisoners in separate areas based on the severity of their criminal acts, the formation of special places for female and juvenile inmates, the layout of healthcare institutions, houses of worship, and working and living quarters for soldiers and officers near the prison region.

As the preceding sections indicated, the Yedikule Central Prison project, which had been suspended owing to the period's financial limitations, was reintroduced in 1898. As a result, from 1893 to 1900, there had been a strong desire to build a central prison in the Ottoman Empire's capital. The choice of the Yedikule Fortress as the location for this central prison is remarkable. The degree of thought and work invested in creating this 'modern,' 'orderly,' and 'excellent' prison in the capital might be considered a sign that this project played an important role in the broader Westernization efforts in the field of criminal reforms. In this context, the application of radial plan type may be understood as adopting a Western building type to overcome a previously unknown design problem. However, the designs for the central prison projects were clearly reevaluated and revised step by step over the course of 10 years.

It can be observed that the project proposal plans began to correspond gradually to the essential requirements of the prison reform. The inclusion of workplaces, a medical station, and administration and service areas in the proposals for Ankara and Istanbul Yedikule Central Prisons demonstrates that these designs were aimed to satisfy the demands presented by the changes that come with prison reform in a large prison complex rather than a single prison structure. Wards were chosen over cells in order to accommodate the expanding amount of inmates while also lowering costs in Ankara Central Prison proposals. It can be stated that despite all of the project proposals presented for the construction of Ankara and Istanbul Yedikule Central Prisons, which contain the necessary spatial configuration arrangement for the prison reform, they could have never been constructed.

Endnotes

[1] Bozkaya, K. (2014), Osmanlı’da Mahbesten Modern Hapishanelere Geçiş Süreci, Akademik Araştırmalar

[2] Adak, Ufuk. “The Politics of Punishment, Urbanization, and Izmir Prison in the Late Ottoman Empire.” Thesis, University of Cincinnati, 2015. page i.

[3] Yıldız, G. (2012), Mapushane: Osmanlı Hapishanelerinin Kuruluş Serüveni (1839-1908), Kitapevi Yayınevi, İstanbul

[4] Yıldız, G.,Mapushane: Osmanlı Hapishanelerinin Kuruluş Serüveni (1839-1908)

[5] Yıldız, G.,Mapushane: Osmanlı Hapishanelerinin Kuruluş Serüveni (1839-1908), 424-430.

[6] Sezer, Selahaddin, and Ceren Katipoğlu Özmen. “Designing Ottoman Prisons in the 19th Century: Ankara Central Prison Projects.” Online Journal of Art and Design 9, no. 2 (April 2021). 81.

[7] Avcı, Y. Osmanlı Hükümet Konakları: Tanzimat Döneminde Kent Mekanında Devletin Erki ve Temsili. Tarih Vakfı Yurt Yayınları.(2016).

[8] Sezer, Selahaddin, and Ceren Katipoğlu Özmen. “Designing Ottoman Prisons in the 19th Century: Ankara Central Prison Projects.” .81.

[9] Sezer, Selahaddin, and Ceren Katipoğlu Özmen. “Designing Ottoman Prisons in the 19th Century: Ankara Central Prison Projects.” .82.

[10] Schull, Kent F. Prisons in the Late Ottoman Empire: Microcosms of Modernity. Edinburgh University Press, 2018. 124.

[11] Schull, Kent F. Prisons in the Late Ottoman Empire: Microcosms of Modernity. 91.

[12] Sezer, Selahaddin, and Ceren Katipoğlu Özmen. “Designing Ottoman Prisons in the 19th Century: Ankara Central Prison Projects.” .84.

[13] Katipoğlu Özmen, Ceren, and Selahaddin Sezer. “Making the Unwanted Visible: A Narrative on Abdülhamid II’s Ambitious Project for Yedikule Central Prison in Istanbul.” ,11.

[14] Sezer, Selahaddin, Ottoman Prison Architecture After Tanzimat Era: Examples of Radial Plan Typologies, [Unpublished M. Arch Dissertation], Çankaya University,(2020),364.

[15] Sezer, Selahaddin, Ottoman Prison Architecture After Tanzimat Era: Examples of Radial Plan Typologies,371.

[16] Yavuz, Y. İmparatorluktan Cumhuriyete Mimar Kemalettin (1870-1927), TMMOB Mimarlar Odası ve Vakıflar Genel Müdürlüğü, Ankara,(2009).

[17] Sezer, Selahaddin, Ottoman Prison Architecture After Tanzimat Era: Examples of Radial Plan Typologies,371.

[18] Sezer, Selahaddin, Ottoman Prison Architecture After Tanzimat Era: Examples of Radial Plan Typologies,372.

FIG. 1 Katipoğlu Özmen, Ceren, and Selahaddin Sezer. “Making the Unwanted Visible: A Narrative on Abdülhamid II’s Ambitious Project for Yedikule Central Prison in Istanbul.” ,374.

FIG.2 Sezer, Selahaddin, and Ceren Katipoğlu Özmen. “Designing Ottoman Prisons in the 19th Century: Ankara Central Prison Projects.” Online Journal of Art and Design 9, no. 2 (April 2021). 81.

FIG. 3 Sezer, Selahaddin, and Ceren Katipoğlu Özmen. “Designing Ottoman Prisons in the 19th Century: Ankara Central Prison Projects.” Online Journal of Art and Design 9, no. 2 (April 2021). 82.

FIG. 4 Sezer, Selahaddin, and Ceren Katipoğlu Özmen. “Designing Ottoman Prisons in the 19th Century: Ankara Central Prison Projects.” Online Journal of Art and Design 9, no. 2 (April 2021). 83.

FIG. 5 Sezer, Selahaddin, and Ceren Katipoğlu Özmen. “Designing Ottoman Prisons in the 19th Century: Ankara Central Prison Projects.” Online Journal of Art and Design 9, no. 2 (April 2021). 840

FIG. 6 Sezer, Selahaddin, Ottoman Prison Architecture After Tanzimat Era: Examples of Radial Plan Typologies, [Unpublished M. Arch Dissertation], Çankaya University,(2020),368.

FIG. 7 Sezer, Selahaddin, Ottoman Prison Architecture After Tanzimat Era: Examples of Radial Plan Typologies, [Unpublished M. Arch Dissertation], Çankaya University,(2020),368.

FIG. 8 Sezer, Selahaddin, Ottoman Prison Architecture After Tanzimat Era: Examples of Radial Plan Typologies, [Unpublished M. Arch Dissertation], Çankaya University,(2020),372.

FIG. 9 Sezer, Selahaddin, Ottoman Prison Architecture After Tanzimat Era: Examples of Radial Plan Typologies, [Unpublished M. Arch Dissertation], Çankaya University,(2020),372.

FIG. 10 Sezer, Selahaddin, Ottoman Prison Architecture After Tanzimat Era: Examples of Radial Plan Typologies, [Unpublished M. Arch Dissertation], Çankaya University,(2020),373.

FIG. 11 Sezer, Selahaddin, Ottoman Prison Architecture After Tanzimat Era: Examples of Radial Plan Typologies, [Unpublished M. Arch Dissertation], Çankaya University,(2020),374.

Further Reading

- Adak, Ufuk. “Central Prisons (Hapishane-I Umumi) in Istanbul and Izmir in the Late Ottoman Empire: In-between Ideal and Reality.” Journal of the Ottoman and Turkish Studies Association 4, no. 1 (2017). https://doi.org/10.2979/jottturstuass.4.1.05.

- Baer, Gabriel, “The Transition to Western Criminal Law in Turkey and Egypt”, Studia Islamica, 45, 1977, 139-158.

- Coşgel, Metin M., Boğaç Ergene, Haggay Etkes, Thomas J. Miceli, “Crime and Punishment in Ottoman Times: Corruption and Fines”, Journal of Interdisciplinary History, XLIII:3, Winter, 2013, 353-376.

- Davison, Roderic H., Reform in the Ottoman Empire (1856-1876), Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963.

- Heyd, Uriel, Studies in Old Ottoman Criminal Law, ed. V.L. Ménage, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973.

- Prostor 28, no. 2 (60) (2020): 360–77. https://doi.org/10.31522/p.28.2(60).11.

- Reports on Conditions in Turkish Prisons, House of Commons Parliamentary Papers, Online, Miscellaneous N.6 (1919), London, 1919.

コメント